Navy Chief Sacrificed His Life and Earned the Medal of Honor Saving 123 Sailors During the Battle of the Coral Sea

Chief Watertender Oscar V. Peterson spent 21 years at sea before May 7, 1942, when Japanese bombs turned the USS Neosho into a burning wreck during the Battle of the Coral Sea. Already wounded from the attack, the 42-year-old sailor crawled alone into several superheated compartments to manually close four massive steam line valves.

Working through searing pain as third-degree burns covered his face, arms and legs, Peterson isolated the engine room steam systems and prevented a catastrophic boiler explosion that would have killed everyone aboard the ship. His actions bought the crippled oiler four more days of life, enough time for rescuers to save 123 men as Japanese planes and submarines prowled the area. Peterson died of his burns six days later and posthumously received the Medal of Honor for sacrificing his life to save his shipmates.

The USS Neosho

The Neosho was a 553-foot Cimarron-class fleet oiler commissioned in August 1939. The ship displaced 7,470 tons and could carry nearly 150,000 barrels of fuel, making it a critical part of the Pacific Fleet’s overseas operations. The crew began referring to her as “The Fat Lady.”

Commander John S. Phillips took command after conversion work on the ship was completed at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in the summer of 1941.

The Neosho soon found itself in its first major battle. On Dec. 7, 1941, the ship was moored at Pearl Harbor’s gasoline dock when Japanese aircraft attacked the fleet. Phillips got his vessel underway without tugs while his crew chopped mooring lines with fire axes. He maneuvered past the capsized Oklahoma while his men fired anti-aircraft weapons at the attacking planes.

According to some reports, his men managed to down one Japanese plane. The Neosho was one of the few ships to get underway that morning. Phillips received the Navy Cross for the action.

A Veteran Chief and the Pacific War

Oscar Verner Peterson was born Aug. 27, 1899, in Prentice, Wisconsin. He enlisted in the Navy on Dec. 8, 1920, and spent more than two decades at sea, rising through the ranks by mastering the complex steam propulsion systems that powered the fleet. By April 1941, when he reported to the Neosho, Peterson had already earned the rank of chief watertender, a senior petty officer responsible for the ship’s boilers and steam lines.

At 42, Peterson was older than most of the Neosho’s crew. He had a wife, Lola, and two sons in Richfield, Idaho. He was exactly the type of experienced, steady hand a ship needed in combat, a veteran who knew his equipment and could be counted on when things went wrong.

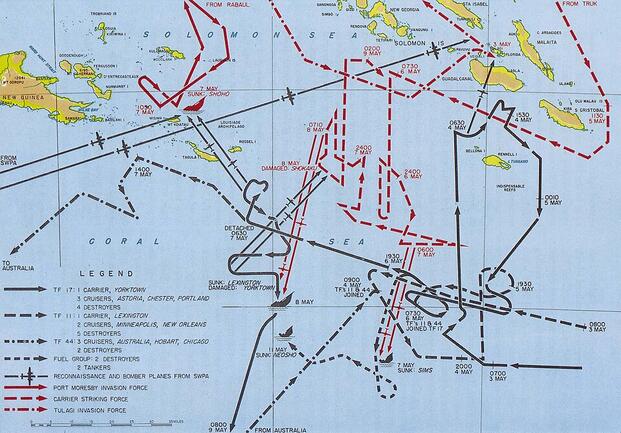

By spring 1942, Japanese forces threatened Australia. Their next objective was Port Moresby on New Guinea, which would put aircraft within striking distance of northern Australia. American code breakers deciphered the Japanese plans. Admiral Chester Nimitz ordered Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s Task Force 17, built around the carriers Yorktown and Lexington, to stop the invasion.

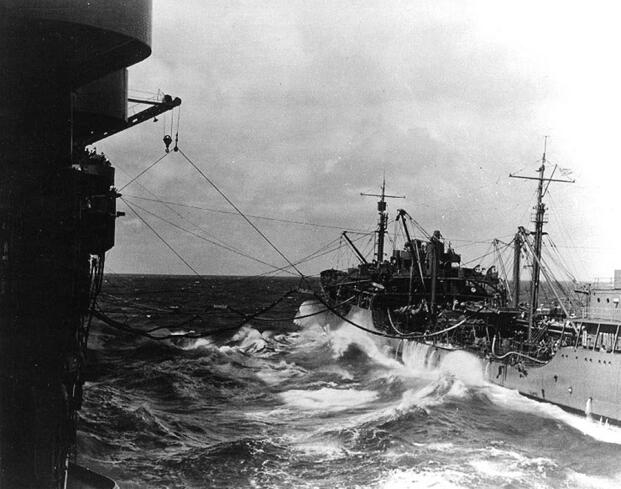

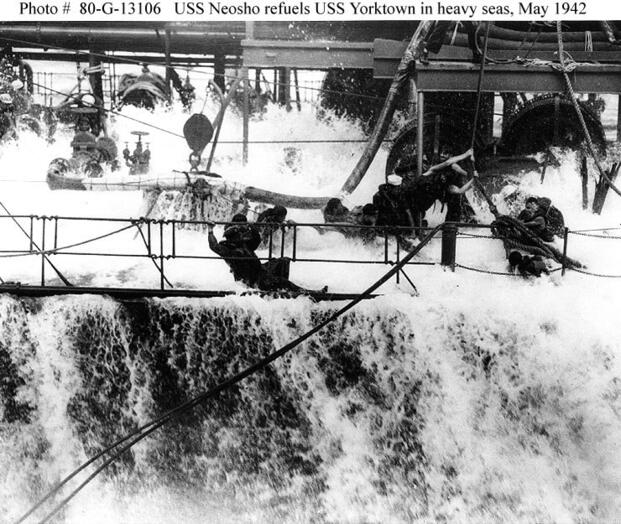

On May 7, the Neosho entered the battle area and refueled the Yorktown approximately 225 miles southeast of New Guinea. The carrier was in dire need of fuel as it participated in the first naval engagement in history where neither fleet actually saw each other. Airplanes launched from carriers on both sides, looking for any enemy vessels in the area.

After completing the mission, Phillips received orders to move to Point Rye, more than 100 miles from the battle. Only the destroyer USS Sims accompanied the oiler as other escorts were urgently needed for the carriers. At 7:20 a.m., two Japanese search planes spotted the ships and erroneously radioed they had found a carrier and escort. Approximately 78 Japanese aircraft launched to attack.

The Attack Against the Neosho

The Japanese aircraft arrived around 10 a.m. and circled for nearly two hours, observing through the clouds before realizing their error. While some planes returned to their ships, several dozen pilots decided to sink both American ships rather than return empty-handed. The attack began just after noon.

The Sims fought heroically, unleashing what anti-aircraft munitions it had, but it stood no chance. Three 500-pound bombs struck in rapid succession, detonating the destroyer’s boilers and magazines. The explosion broke the ship in two. It sank within minutes, taking 237 men down with it. Only 15 sailors survived the sinking and were rescued by the Neosho.

With the Sims gone, the Japanese dive bombers concentrated on the oiler. Phillips maneuvered desperately while his gunners fought back with one 5-inch gun, four 3-inch antiaircraft guns, and several 20mm machine guns. The Japanese attacked from multiple directions, overwhelming the defenses.

Seven 550-pound bombs scored direct hits on the main deck, stack deck, fireroom, and fuel tanks. Eight near misses nearly broke the hull plates. A burning Val dive bomber, hit by anti-aircraft fire, crashed into gun station No. 4, killing the entire gun crew and spreading fires across the deck.

Phillips later reported his gunners shot down three aircraft and damaged four more. But the damage to the ship was catastrophic. The seven direct hits ignited fires in fuel compartments. Flooding poured into the engine room. The ship lost all propulsion and listed 30 degrees to port. At least 20 men died immediately. Many more were wounded.

Even worse, the ship was in danger of exploding at any moment.

At 12:18 p.m., the attack ended. Phillips surveyed the damage and gave orders to prepare for an evacuation. But many crew members, having just watched the Sims sink in minutes and knowing the oiler could explode, panicked and abandoned ship immediately. Within minutes, 68 men had already abandoned ship and drifted away. Phillips regained control and made the decision to keep his remaining crew of 16 officers and 91 enlisted men aboard the ship to fight for survival.

Peterson’s Heroic Acts

During the attack, Peterson commanded a repair party in the crew’s mess compartment adjacent to the fireroom. His assignment was to close four main steam line bulkhead stop valves if battle damage required isolating the engine room. These massive valves controlled steam flow throughout the ship’s propulsion system.

He knew that if the boilers were damaged and fires were spreading, the valves needed to be closed immediately.

When a bomb exploded in the fireroom, the blast tore open the iron door between the fireroom and mess compartment. The explosion knocked Peterson down and burned his face and hands. Every member of his repair party was wounded or killed by the blast, either by shrapnel or escaping steam that poured through the ruptured door.

Peterson knew what had to be done. The steam lines carried pressure hot enough to strip flesh from bone. If left open, uncontrolled steam would build throughout the system with no way to release it safely. Fires could reach the steam lines under pressure, causing catastrophic ruptures. Worst of all, those fires would reach the fuel tanks while steam-powered pumps kept systems active, leading to a massive explosion that would kill everyone aboard.

Working alone, Peterson made his way into the fireroom trunk over the forward boilers. He waited for the escaping steam to dissipate enough to reach the valves without being instantly killed. The heat was almost unbearable. Metal surfaces were too hot to touch. The air itself burned his lungs.

Each valve, warped by intense heat, required tremendous effort to shut manually. Peterson forced the first valve closed despite the searing pain. Then he closed the second one as his hands blistered and bled. The third valve was damaged in the explosion. He threw his full weight against it to close it.

The fourth valve was hardest one to reach, positioned deep within the compartment. Peterson suffered even more severe burns to his head, arms and legs as he struggled to close it. But he succeeded, preventing the explosion that would have sent the Neosho and her crew to the bottom of the ocean.

Other Heroes on the Ship

Peterson was not alone in saving the ship. Executive officer Lieutenant Commander Francis J. Firth coordinated damage control throughout the ship. He organized teams to fight fires, pump out flooded spaces, and shore up damaged bulkheads. Firth worked tirelessly for four days, moving from compartment to compartment to direct repairs.

Engineering officer Lieutenant Louis Verbrugge also helped keep the ship afloat. The ship was listing 30 degrees and was in danger of capsizing. Verbrugge identified which tanks to flood to counteract the list. His counterflooding operations brought the ship to a more stable angle, preventing capsizing while also keeping the ship from breaking apart further.

Machinist’s Mate First Class Harold Bratt and Machinist’s Mate Second Class Wayne Simmons fought numerous fires and prevented flooding in the engine spaces for hours in smoke-filled compartments under the constant danger of an explosion. Both men showed exceptional courage working below decks, where escape would be impossible if the ship sank.

All of these men received Silver Stars for their leadership and courage.

With the ship’s medical officer dead, Pharmacist’s Mate First Class William J. Ward took over medical duties. Chief Pharmacist’s Mate Robert W. Hoag assisted him. Together, they tended to dozens of wounded men with limited supplies, performing surgeries and treating severe burns for men injured in the attack or by fires, as well as the surviving crewmembers from the Sims.

Ward received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

Four Days Adrift at Sea

Phillips faced a nightmare scenario. His ship was dead in the water, listing heavily, on fire and loaded with thousands of barrels of volatile fuel. The crew had radioed their position but accidentally transmitted coordinates 30 miles off. Search aircraft looked in the wrong area while most of the American fleet remained engaged against the Japanese

The crew worked through the night and following days battling fires in multiple compartments. Teams used portable pumps and buckets when the main systems failed. They gradually controlled the blazes through exhausting physical effort.

The men worked in rotating shifts to pump out flooding, shore up damaged bulkheads, and monitor for structural failure. The damaged hull creaked and groaned constantly, threatening to break in two.

The crew only stopped to commit fallen shipmates to the sea in quick funeral ceremonies before returning to their duties.

Meanwhile, 120 miles away, the main carrier battle raged. American aircraft sank the Japanese carrier Shoho on May 7. The next day, Japanese aircraft sank the carrier Lexington and damaged the Yorktown.

The crippled Neosho drifted helplessly through waters patrolled by Japanese submarines and aircraft. Discovery after surviving the previous engagement would mean certain death, the crew could do nothing to defend themselves or maneuver away. Every hour increased the chance of being spotted and hit by another enemy attack. Yet the crew never stopped fighting to keep their ship afloat.

On May 11, a Royal Australian Air Force plane spotted the vessel, followed by an American PBY. At 1 p.m., the destroyer USS Henley arrived and evacuated 123 survivors, including 109 from the Neosho and 14 from the Sims. Six crew members had died waiting for rescue.

Phillips requested that the Henley scuttle his ship. After two torpedoes and 146 rounds of 5-inch gunfire, the Neosho finally went under at 3:22 p.m. on May 11.

The Ultimate Sacrifice

Peterson was barely alive when he was evacuated. The burns covering his head, arms, and legs were severe. He died on May 13, 1942, and was buried at sea. Two other Neosho sailors died aboard the Henley from their injuries.

The ordeal wasn’t over for everyone. The 68 men who drifted away on rafts floated for nine days without food or water. On May 16, the destroyer USS Helm found four men clinging to a raft. Two died shortly after rescue. The other 64 were never found.

Peterson received the Medal of Honor posthumously on Dec. 7, 1942. Because of the ongoing intensity of the war, his widow received the medal in the mail with no ceremony. In 1943, the Navy commissioned the destroyer escort USS Peterson in his honor.

In April 2010, the Navy finally held a proper ceremony. Rear Admiral James A. Symonds presented the Medal and a 48-star flag to Peterson’s son, Fred, in Richfield, Idaho. More than 800 people attended.

Phillips received the Silver Star and retired as a rear admiral after the war. The other decorated crew members, including Firth, Verbrugge, Bratt, Simmons, Ward, and Hoag, all survived the conflict. The Neosho received two battle stars for its short WWII service. A new Neosho-class oiler was commissioned in 1954, sponsored by Mrs. John S. Phillips.

Without Peterson closing those valves, the Neosho would have exploded before rescue arrived. His sacrifice gave 123 men four more days of survival and a chance to return home.

Story Continues

Read the full article here