America’s Game: How Army and Navy Built One of the Most Legendary College Football Rivalries

Navy started playing organized football in 1879, when first-classman William John Maxwell formed the Naval Academy’s first team. The squad practiced before reveille and after drills, against direct orders from the academy superintendent who had banned the sport.

By 1890, Navy needed a similar opponent, but Army didn’t have a football team. When Navy requested a friendly game, Cadet Dennis Mahan Michie convinced West Point leadership to create a team.

On November 29, 1890, the teams met on the Plain at West Point for the first time. The 271 members of the Corps of Cadets each contributed 52 cents to cover half of Navy’s travel costs. Navy arrived by ferry and according to some legends, grabbed a goat from an Army NCO’s quarters to use as their mascot. Other legends allege that the officers of the USS New York gifted the Midshipmen their ship’s goat mascot. Either way, Bill the Goat became Navy’s official mascot.

Navy dominated 24-0 in front of roughly 1,000 spectators.

Michie recruited coach Harry Williams from nearby Newburgh to lead the team in practice going forward. When Army traveled to Annapolis in 1891, the Black Knights crushed Navy 32-16. The rivalry was born.

Dennis Michie never saw the rivalry become the legend it is now. Captain Michie was killed during the Spanish-American War on July 1, 1898, shot by a Spanish marksman during the Battle for Santiago at just 28 years old.

Early Rivalries, Suspensions, and Resumptions

In the 1893 meeting, Navy Admiral Joseph Mason Reeves made history by wearing what’s widely regarded as the first football helmet—a leather contraption made by an Annapolis shoemaker after a Navy doctor warned another head injury could cause death or permanent disability.

After that game, an argument between an Army general and a Navy admiral escalated into a brawl between fans on both sides. President Grover Cleveland intervened, issuing orders that effectively prevented the teams from playing each other from 1894 through 1898.

The game resumed in 1899 in Philadelphia. For the first time, Army chose the mule as the team mascot when a quartermaster officer chose a white mule to match the Navy goat. The first “official” Army mule, Mr. Jackson, later arrived at West Point in 1936.

Navy’s 1906 victory, 10-0, became one of the most historic. Percy Northcroft kicked a 43-yard field goal, and Jonas Ingram caught a 20-yard touchdown pass to win the game. After the win, Navy unveiled “Anchors Aweigh” which later became the Navy’s official song.

In 1909, West Point Cadet Eugene Byrne unfortunately died from injuries sustained in an October game against Harvard. Army canceled the remainder of its season in mourning. World War I canceled the 1917 and 1918 games. Disputes over player eligibility rules canceled the 1928 and 1929 matchups.

Since 1930, the rivalry has remained unbroken for 95 consecutive years. Through 125 meetings, Navy leads 63-55-7. Though Army has won six of the last eight.

Future Generals on the Gridiron

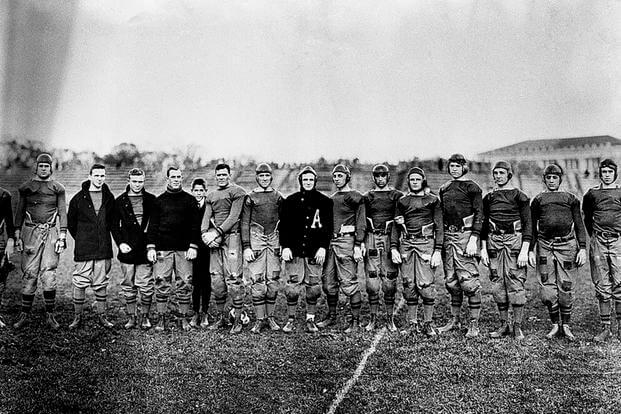

The 1912 Army team included halfback Dwight D. Eisenhower, who started three games before a career-ending knee injury against Tufts. The New York Times called him “one of the most promising backs in Eastern football.”

Omar Bradley also played on that squad. Both belonged to West Point’s Class of 1915, later known as “the class the stars fell on” for producing 59 generals. Bradley became a five-star general and the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

During the Battle of the Bulge, Bradley reminded Eisenhower of a lesson their coach Ernest Graves Sr. had taught them in 1912, “If things break badly or go against you, stay with it all the harder.”

That 1912 team also included six other generals who would go on to achieve great feats in both World Wars. William Hoge, Geoffrey Keyes, Leland Hobbs, Leland Devore, Vernon Prichard, and Robert Neyland, who later became a College Football Hall of Fame coach at Tennessee.

Even Douglas MacArthur served as Army’s team manager in 1899. He graduated from West Point first in his class in 1903. He wrote that on “the fields of friendly strife are sown the seeds that on other days, upon other fields, will bear the fruits of victory.”

Navy’s William “Bull” Halsey played for the Midshipmen in the early 1900s before directing naval operations in the Pacific during World War II. Other famous admirals who played football for Navy include Thomas Hamilton, John Stuffelbeem, and Don Whitmore.

Medal of Honor Recipients

Eleven service academy football players later received the Medal of Honor—six from Navy, five from Army.

Navy’s Allen Buchanan lettered in 1898 but never faced Army—his playing years fell during the 1894-1898 suspension. He earned the Medal of Honor on April 21, 1914, during the Battle of Vera Cruz.

Two other Navy football players earned the award during the same Mexican campaign in April 1914, Jonas Ingram, who played fullback from 1903 to 1906 and scored the only touchdown in the 1906 Army-Navy game, and Frederick McNair Jr.

Carlton Hutchins played for Navy from 1922 to 1925. He received a peacetime Medal of Honor in 1938 after staying at the controls of his damaged PBY-2 seaplane to give his crew time to parachute to safety off the California coast during training.

Richard Antrim, a POW in the Dutch East Indies, saved a fellow officer’s life by taking a beating meant for him. Harold Bauer, a Marine aviator at Guadalcanal, engaged an entire Japanese squadron alone and destroyed four enemy planes before his fuel ran out.

Army’s five recipients included Douglas MacArthur, who received his Medal for defending the Philippines in World War II. Robert Cole led a bayonet charge across open ground near Carentan on D-Day. Leon Vance Jr. flew a crippled bomber back over the English Channel on one engine with his foot nearly severed.

Samuel Coursen engaged in hand-to-hand combat in Korea—seven enemy dead were found in the emplacement when his body was recovered. Frank Reasoner was killed in Vietnam running to aid his wounded radio operator under heavy fire.

Medal of Honor recipients have also participated in pregame ceremonies. Before the 2010 game, three Army recipients—including Staff Sergeant Salvatore Giunta, the first living recipient from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—joined three Navy recipients for the coin toss.

Presidential Attendance at the Game

Theodore Roosevelt became the first sitting president to attend in 1901, establishing the game as a national event. He attended again in 1905. Harry S. Truman set the record for attendance, watching all but one game from 1945 to 1952, missing only the 1951 matchup while on vacation. The former World War I artillery captain understood the game’s significance.

In total, 10 sitting presidents have attended the game including Woodrow Wilson (1913), Calvin Coolidge (1924), Gerald Ford (1974), Bill Clinton (1996), George W. Bush (2001, 2004, 2008), Barack Obama (2011), and Donald Trump (2018, 2019, 2020). Trump also attended as president-elect in 2016 and 2024.

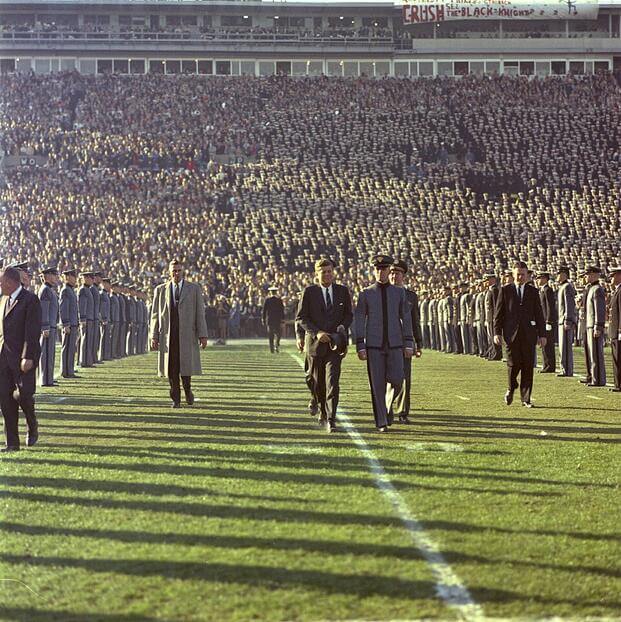

John F. Kennedy was particularly fond of the rivalry. The former PT boat commander who earned the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for heroism in World War II attended the 1961 and 1962 games. Presidents typically sit at midfield, alternating between the Army and Navy sides at halftime.

When Both Teams Dominated the Sport

For much of the first half of the 20th century, Army and Navy dominated college football. The 1926 game at Chicago’s Soldier Field drew 110,000 spectators. Both teams entered undefeated—Navy at 9-0, Army at 8-0-1.

Army coach Biff Jones started his second unit to “soften” Navy. The strategy backfired as Navy jumped to a 14-0 lead. Army’s starters rallied for a 21-14 fourth-quarter lead, but Navy’s Tom Hamilton executed a reverse that allowed Alan Shapley to score a late touchdown. Hamilton drop-kicked the extra point for a 21-21 tie. Because Army already had one tie on its record, Navy claimed a share of the 1926 national championship.

Despite WWII, the 1944 Army team had assembled what General MacArthur called “the greatest of all Army teams.” Led by future Heisman winners Felix “Doc” Blanchard and Glenn Davis, the Black Knights entered ranked No. 1 while Navy stood at No. 2. The December 2 game in Baltimore drew 70,000 fans for a War Bond drive that raised $58.6 million. Army won 23-7, snapping a five-game losing streak to Navy.

In 1945, both teams again entered undefeated, ranked No. 1 and No. 2. Army raced to a 20-0 first-quarter lead and won 32-13. Those Army teams went undefeated from 1944 through 1946 while winning three straight national titles.

Five Heisman winners have played in Army-Navy games including Blanchard (1945), Davis (1946), Pete Dawkins (Army-1958), Joe Bellino (Navy-1960), and Roger Staubach (Navy-1963). As college football evolved, both academies found it difficult to compete due to admissions standards and service obligations. Since 1963, only five games have featured both teams entering with winning records.

The 1963 game became one of the most poignant in the rivalry’s history. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, eight days before the scheduled kickoff forcing both teams to contemplate cancelling the game. Jacqueline Kennedy urged both academies to proceed, feeling her husband would have wanted it to happen. The game moved to December 7—the 22nd anniversary of Pearl Harbor. More than 102,000 spectators filled Philadelphia’s Municipal Stadium.

Navy entered 9-1 behind quarterback Staubach, who had just been named Heisman Trophy winner. Army’s opening touchdown drive featured the first use of instant replay in American television. Navy won 21-15. Staubach served in the Navy before a Hall of Fame career with the Dallas Cowboys. Army quarterback during the game, Rollie Stichweh, later served five years in Vietnam with the 173rd Airborne Brigade.

Modern Era Football Milestones

The 1964 game marked another milestone when Navy sophomore Calvin Huey became the first African-American to play in the series. Although Army won 11-8, Huey completed four passes.

Through the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, the rivalry remained fierce. Army won seven of nine games from 1984 to 1992, but Navy answered with six consecutive victories from 1993 to 1998.

Navy dominated the modern era with a 14-game winning streak from 2002 to 2015, the longest in series history. Led by quarterback Keenan Reynolds, who set an NCAA record with 88 rushing touchdowns, the Midshipmen won by an average margin of 25.7 points during the first nine games. Reynolds finished fifth in Heisman voting in 2015.

Army finally broke through on December 10, 2016, with a 21-17 victory. Army has since won six of eight meetings, including a 20-17 double-overtime game in 2022—the first overtime game in the rivalry’s history. Only seven games in the entire series have been decided by three points or fewer.

Navy won the 2024 game 31-13, the 125th meeting between the academies.

Traditions of the Army-Navy Game

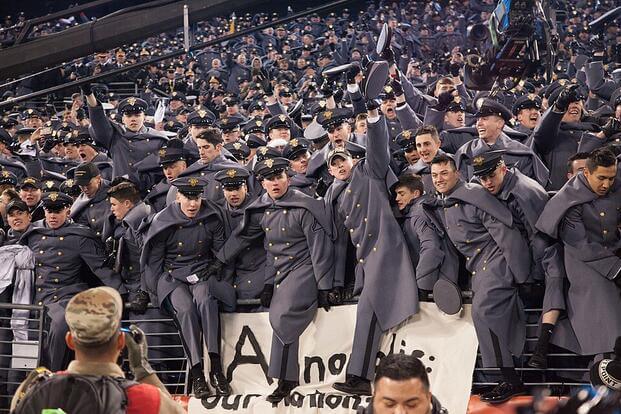

The pregame march-on has both student bodies enter the stadium in military formation. Every cadet and midshipman participates. The prisoner exchange has become a tradition since the Service Academy Exchange Program began. Cadets spending the fall semester at Annapolis and midshipmen studying at West Point are ceremonially released before kickoff. The USMA first captain leads the midshipmen to midfield, while the USNA brigade commander brings out the West Point cadets.

Military jets conduct flyovers. When the president attends, Air Force One sometimes joins the formation. The Navy’s Leap Frogs and Army’s Black Knights parachute teams often land on the field. Cadets and Midshipmen usually bring signs poking fun at each other with witty football jokes and pop-culture references.

After the game, both teams gather at midfield. They face the losing team’s students and sing that alma mater together. Then they turn to face the victors and sing the winning school’s song. Within years, many of these competitors could serve on the same side in combat.

Service academy alumni remain standing at attention after other fans leave, hands over hearts as both songs play.

Alternate Uniforms and Military Tributes

In 2008, Nike created the first special uniforms for the game. Army wore camouflage helmets and pants with “WEST POINT” stenciled down the legs, paired with a black jersey featuring camo numbers. Navy wore white jerseys with blue and gold epaulets inspired by historic Navy service uniforms. Starting in 2011, both teams began regularly unveiling elaborate alternates.

Since 2016, Army has worked with Nike and West Point’s Department of History and War Studies to honor specific military units such as the 82nd Airborne (2016), 10th Mountain Division (2017), 1st Infantry Division (2018), 1st Cavalry Division (2019), 25th Infantry Division (2020), Special Operations (2021), 1st Armored Division (2022), 3rd Infantry Division (2023), and 101st Airborne (2024).

Navy’s approach has showcased aviation and naval warfare including aircraft carriers (2015), Blue Angels (2017), NASA astronauts—54 Naval Academy graduates became astronauts, more than any other institution (2022), submarine force (2023), and Jolly Rogers fighter squadron (2024).

The 2025 game marks both services’ 250th anniversaries. Army’s marble-patterned white uniforms match Arlington National Cemetery headstones, with purple accents referencing the Purple Heart. Navy’s design honors the USS Constitution with copper helmets—a nod to the ship’s copper-sheathed hulls.

The Legacy of the Army-Navy Game

Nearly 25 percent of the 1,300 men who have worn Army’s gold and black have risen to at least brigadier general. Forty Hall of Fame players have played in the game, along with nine Hall of Fame coaches. The rivalry has produced five Heisman Trophy winners and numerous professional players, including Roger Staubach’s Hall of Fame tenure with Dallas.

Navy joined the American Athletic Conference in 2015. Army followed in 2024. The Army-Navy game remains an out-of-conference contest. Since 1972, the game concludes the competition for the Commander-in-Chief’s Trophy, awarded to the service academy with the best record among Army, Navy, and Air Force.

For most players, the Army-Navy game marks their last time in pads. For the seniors, it’s typically their final competitive game before commissioning as officers. Within months, they report to their first duty stations. Some lead platoons in combat. Some command ships or fly fighter jets. Some, like Dennis Michie, make the ultimate sacrifice.

Millions of Americans tune in or follow the scores to see which team will come out on top each year, including thousands of service members deployed overseas who stream the game from remote bases and even combat zones.

The rivalry has survived brawls between admirals and generals, wartime restrictions, tragic deaths, and college football’s evolution into a billion-dollar industry where service academy players compete without scholarships while carrying full academic and military training loads.

In 2025, the National Football Foundation honored the Army-Navy game with the Distinguished American Award, recognizing it as a national treasure representing courage, commitment, and service.

The 126th meeting is scheduled for December 13. After 135 years, Army-Navy remains America’s Game.

Story Continues

Read the full article here