Operation Hailstone: The US Navy’s Devastating 1944 Raid on Truk Lagoon

Aviation Radioman 1st Class Dave Cawley sat in the rear seat of his SBD Dauntless dive bomber aboard the USS Enterprise on the morning of Feb. 17, 1944, preparing for the most dangerous mission of his life. His target was Truk Lagoon, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s most fortified forward base in the Pacific.

“For the previous two years of the war, the very thought of approaching Truk seemed fatal,” Cawley later recalled.

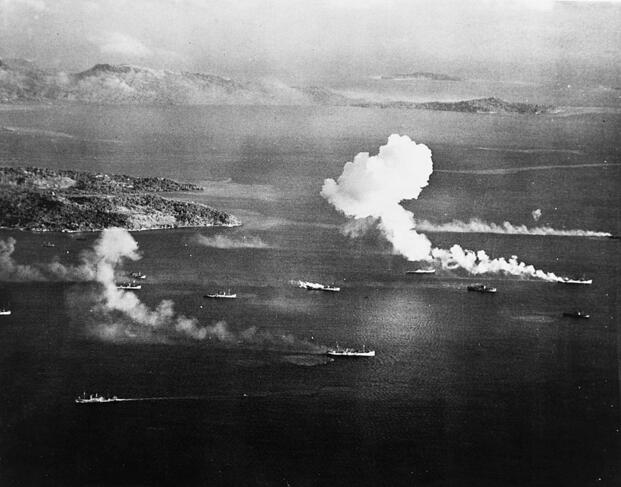

Within 48 hours, Cawley and hundreds of other Navy aircrewmen would prove that fear unfounded. Operation Hailstone, the two-day carrier assault launched 82 years ago this week, demolished Japan’s largest overseas naval installation and sent more than 40 ships beneath the waves. It was the first time a major portion of the U.S. fast carrier force operated independently as a raiding strike unit, untethered from an amphibious landing.

Japan’s Fortress at Truk

Truk Lagoon sits roughly 1,000 miles northeast of New Guinea in the western Pacific. A massive barrier reef some 40 miles across encircles dozens of volcanic islands. Japan seized the atoll from Germany during World War I and held it under a League of Nations mandate.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, Tokyo quietly transformed Truk into a major military base. Five airstrips, seaplane facilities, submarine repair shops and fleet anchorages turned the lagoon into the operational hub of the Combined Fleet.

The base also housed storage for more than 77,000 tons of fuel oil, the largest Japanese depot outside the home islands. By February 1944, between 10,000 and 12,000 army and navy troops garrisoned the atoll. Coastal guns covered all five lagoon entrances, which were also rigged with electrically controlled mines.

Despite all that firepower, the base had only 40 anti-aircraft guns, and none were equipped with fire control radar.

Allied planners called it the “Gibraltar of the Pacific.” No American force had dared to strike it.

A New Kind of Carrier Force

That changed in early 1944. The U.S. Navy’s industrial surge had produced a carrier fleet unlike anything in history. Rear Adm. Marc Mitscher’s Task Force 58 included five fleet carriers and four light carriers armed with more than 500 combat aircraft. Seven battleships, cruisers, destroyers and submarines bolstered them.

Mitscher had taken command of the fast carriers just weeks earlier, replacing Rear Adm. Charles Pownall, whom Adm. Chester Nimitz’s headquarters deemed too cautious. Mitscher ran things differently.

“I tell them what I want done. Not how!” he once said of his leadership approach.

Vice Adm. Raymond Spruance, the Fifth Fleet commander and victor at Midway, ordered the assault on Truk to neutralize the base ahead of the upcoming invasion of Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands. Japanese aircraft at Truk could threaten that operation, and the base also served as a stopover for ferrying replacement warplanes to Rabaul.

Adm. Mineichi Koga, commander of the Combined Fleet, had recognized Truk’s growing vulnerability. After Marine Corps PB4Y-1 Liberator reconnaissance planes were spotted over the lagoon in early February, Koga pulled his capital ships, including battleships, heavy cruisers and carriers, roughly 1,200 miles west to Palau.

They would never return.

Total Surprise

The operation’s first kill came even before carrier planes launched. The light cruiser Agano, badly damaged months earlier at Rabaul, had departed Truk on Feb. 15 under escort by the destroyer Oite, limping toward Japan on only two of her four propellers.

The submarine USS Skate intercepted Agano roughly 160 miles north of the atoll on the afternoon of Feb. 16 and put two torpedoes into her starboard side. The cruiser burned through the night and sank early the next morning. Oite rescued 523 of Agano’s crewmen and turned back toward Truk.

Only days earlier on Feb. 12, three of TF 58’s four carrier task groups departed Majuro for Truk. On the morning of Feb. 17, Mitscher’s carriers launched their first fighter sweep 90 minutes before dawn.

The Japanese were caught completely off guard. Pilots from the 22nd and 26th Air Flotillas were on shore leave, having relaxed after weeks of heightened readiness following American reconnaissance overflights. The atoll’s radar was blind to anything flying below a certain altitude, and the telephone lines connecting defensive positions worked poorly.

American F6F Hellcat fighters arrived over Eten, Param, Moen and Dublon islands before Japanese pilots could get airborne.

More than 300 Japanese planes sat on the ground across the atoll. Only about half were operational. American fighters tore through those that managed to take off and strafed dozens more on the ground. By midday, roughly two-thirds of Japanese air strength at Truk had been wiped out. The airstrips themselves were cratered beyond use.

Among those watching the destruction from the ground was Maj. Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, the Marine Corps ace and Medal of Honor recipient. Boyington had been a prisoner of war since being shot down over Rabaul a month earlier. His captors flew him into Truk just as the first strikes began. He was shoved into a concrete slit trench while a Hellcat destroyed the transport plane that had carried him in.

Avenger torpedo bombers from Enterprise and Intrepid followed close behind, hitting Eten’s runways and Moen’s seaplane facilities with fragmentation and incendiary bombs. With Truk’s air defenses shattered, American strike aircraft turned their full attention to the lagoon.

Mauling the Japanese Fleet

Koga’s heavy warships were gone, but the lagoon was still packed with merchant vessels, tankers, transports and auxiliary warships. Many sat at anchor with no air cover, defended only by shore-based anti-aircraft batteries. American aircrews were disappointed that the big prizes had fled. They wanted capital ships. But there was still plenty to destroy.

Lt. James D. Ramage, executive officer of Bombing Squadron 10 aboard Enterprise, led repeated dive-bombing strikes into the lagoon. He sank the damaged fleet oiler Hoyo Maru and directed attacks against other shipping targets throughout the day.

One of the single most devastating moments came when Lt. James Bridges of Torpedo Squadron 6, flying off Intrepid, put a torpedo into the auxiliary cruiser Aikoku Maru. The 10,000-ton vessel was packed with ammunition and carried nearly 1,000 soldiers and crew. The torpedo triggered a catastrophic secondary explosion that tore the ship apart and sank her almost instantly.

Bridges and his two crewmen were caught in the blast. Their aircraft was never recovered.

Ships that tried to flee through the atoll’s North Pass fared no better. The light cruiser Katori, auxiliary cruiser Akagi Maru, destroyer Maikaze and other Japanese vessels attempted to break out together. American bombers hit the group repeatedly. Cawley, returning to Enterprise after a strike, spotted the damaged Katori from the air.

“When I sighted the cruiser, she was low in the water and barely moving. Since we were without bombs and ammo, I opened up on guard channel, saying, ‘Any strike leader from 51-Bobcat, there is a damaged Japanese cruiser just to the north of the lagoon. Come sink it,'” Cawley recalled.

Spruance wanted the battleships to finish it. Mitscher personally spoke up and said, “Bobcat leader, this is Bald Eagle. Cancel your last. Do not, repeat, do not, sink that ship.”

Help arrived almost immediately. Spruance had taken personal charge of Task Group 50.9, which included the battleships Iowa and New Jersey and the heavy cruisers Minneapolis and New Orleans. The surface force circled Truk, bombarding shore positions and hunting fleeing enemy ships. Iowa’s 16-inch guns finished off the crippled Katori. American cruisers sent Maikaze to the bottom.

Only the destroyer Nowaki escaped, surviving a near-miss from New Jersey at more than 20 miles. It marked the only time in their careers that Iowa and New Jersey fired their main batteries at enemy warships.

The Night Raid

As darkness fell on Feb. 17, Lt. Cmdr. Bill Martin of Torpedo Squadron 10 launched an operation that had never been attempted. Twelve TBF Avengers catapulted off Enterprise for a low-level, radar-guided night bombing run against Japanese shipping still in the lagoon.

Martin had spent months lobbying senior Navy leadership to prove that carrier-based night strikes were viable. His crew, known as the “Buzzard Brigade,” had trained relentlessly in instrument flying and airborne radar techniques. The Avenger was the only carrier plane in the fleet large enough to carry an operational radar unit.

Each pilot navigated by radar, picking out targets among the coral islets that cluttered the screen. They sank roughly one-third of the total enemy shipping tonnage destroyed during the entire two-day operation.

Cliff Largess, one of the 12 pilots who flew that mission, described it decades later at a 2009 Veterans Day ceremony in Jamestown, New York.

“We took off in the dead of night. The results were spectacular,” he said. “We had the evidence that night flights could be done successfully. The approach caught on, and within a year, most of the aircraft could fly at night. We were the pioneers.”

The Japanese struck back late on Feb. 17. Between roughly 9 p.m. and midnight, small groups of bombers from Truk and Formosa probed the carrier task groups’ defenses. A single twin-engine bomber from the 755th Naval Air Group penetrated the screen and drove a torpedo into Intrepid’s starboard quarter. The hit killed 11 sailors and jammed the carrier’s rudder. Intrepid limped back to the United States for repairs and missed the next six months of the war.

Strikes resumed on Feb. 18. The destroyer Oite arrived at the lagoon’s entrance that day. TBF Avengers caught Oite as she attempted to re-enter the pass. A torpedo broke the ship in half. She sank within minutes, taking all 523 Agano survivors and most of her own crew to the bottom.

By the time Mitscher recalled his aircraft, the damage was overwhelming.

Losses on Both Sides

American pilots destroyed roughly 250 Japanese aircraft and sank approximately 200,000 tons of shipping over those two days. The losses included light cruisers Katori and Naka, four destroyers, two submarine tenders, an aircraft ferry, 32 merchant ships and several fleet oilers.

About 4,500 Japanese servicemen were killed. Some 17,000 tons of stored fuel were also destroyed.

The United States lost 25 aircraft and 35 servicemen.

The tonnage sent to the bottom at Truk amounted to roughly 10 percent of all Japanese merchant shipping lost across the entire Pacific during the preceding eight months. The destruction of precious fleet tankers crippled the Imperial Navy’s ability to fuel operations, a shortage that became painfully obvious during the Battle of Leyte Gulf eight months later. Unlike Pearl Harbor, where U.S. oil storage tanks and repair yards survived the Japanese attack, Truk’s fuel reserves and infrastructure were gutted.

Fleet Adm. Nimitz summarized the outcome bluntly.

“The Pacific Fleet has returned at Truk the visit made by the Japanese Fleet at Pearl Harbor,” he said.

The success of Hailstone convinced the Joint Chiefs that Truk could be bypassed rather than invaded. The atoll’s garrison was marooned.

The Japanese high command responded to the disaster by relieving Vice Adm. Masami Kobayashi of his command of the 4th Fleet two days after the raid. His replacement was Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo, the same officer who had commanded the Japanese carrier strike force at Pearl Harbor. The architect of that 1941 attack now presided over the smoldering wreckage of Japan’s own premier Pacific base.

Mitscher sent carriers back in late April, hammering what remained. Few worthwhile targets survived. By late 1944, the troops stranded on Truk spent most of their time growing food in a losing fight against starvation and tropical disease.

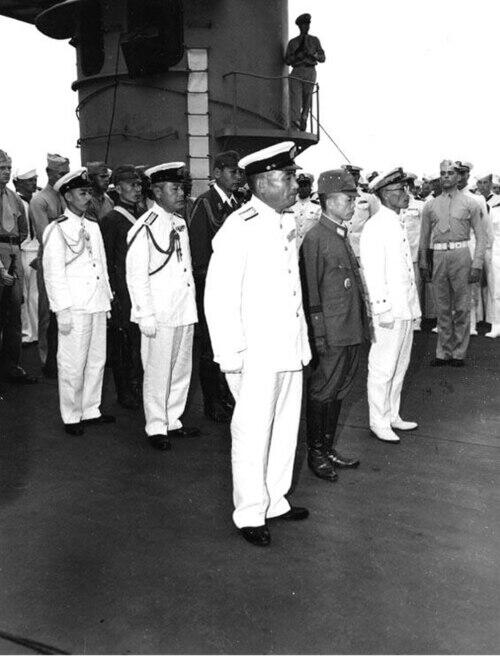

Historian David Hobbs later described the garrison as having been “reduced to starving impotence.” The Japanese commander and his staff formally surrendered aboard the heavy cruiser Portland in Truk’s lagoon on Sept. 2, 1945.

The Legacy 82 Years Later

Operation Hailstone rarely receives the recognition given to Midway or Iwo Jima. A 2024 study in the Journal of Maritime Archaeology noted that Truk “has not received significant historical examination” because it was bypassed and considered a success with acceptable losses.

The ships that sank in 1944 created one of the world’s most extraordinary underwater sites. More than 60 wrecks sit on the floor of what is now called Chuuk Lagoon, their hulls covered with coral.

French explorer Jacques Cousteau brought global attention to the site in a 1969 documentary. The Federated States of Micronesia has designated the wrecks as protected monuments and war graves. Divers still make pilgrimages on the anniversary every February.

Eighty-two years after Hailstone, 35 American servicemen from the February 1944 raids and as many as 225 from later attacks on Truk remain missing in action.

In 2024, researchers from Project Recover located three U.S. aircraft in the lagoon for the first time. Each was crewed by servicemembers still listed as MIA.

The fleet resting at the bottom of Chuuk Lagoon are what remain of an overextended empire that faced an increasingly powerful U.S. Navy. For two days in February 1944, Task Force 58 proved that no Japanese base in the Pacific was beyond reach of American forces.

Read the full article here