The Hidden Benefits of Shooting Suppressed

Most conversations about suppressors fixate on decibel reduction. People often cite OSHA standards and hearing damage thresholds when discussing numbers like 130 dB versus 160 dB. These metrics matter, certainly, but they only tell part of the story.

The real advantage of shooting with a suppressed firearm extends far beyond what a sound meter captures. It involves the complete physiological experience of shooting and how your body responds to the complex forces generated when a firearm discharges.

I’ve spent enough time behind both suppressed and unsuppressed rifles to recognize something the decibel charts don’t explain. After a day at the range with a suppressed rifle, I feel fundamentally different than after shooting unsuppressed, even when wearing quality hearing protection in both scenarios.

The difference isn’t just about preserved hearing. It’s about reduced flinch response, improved focus, less physical fatigue or soreness, and enhanced shooting performance that compounds over time.

The Shockwave Nobody Talks About

When an unsuppressed firearm discharges, the muzzle blast creates more than an audible sound. It generates a physical shockwave that impacts your body, whether you’re wearing hearing protection or not. This concussive force radiates outward from the muzzle, hitting your face, chest, and sinuses with measurable pressure. Electronic earmuffs and foam plugs protect your eardrums from acoustic damage, but they do absolutely nothing against this blast wave.

Muzzle brakes exacerbate this phenomenon even further. While they effectively reduce felt recoil by redirecting propellant gases, they dramatically increase the concussive blast directed toward the shooter and anyone standing nearby. A braked rifle might be easier to control, but the trade-off is a sharper, more intense pressure wave that hits you harder with each shot.

The physiological response to repeated shockwaves is subtle but cumulative. Your body recognizes the blast as a threat. Over time, you can develop an unconscious flinch response that has nothing to do with noise and everything to do with this physical assault. I’ve watched experienced shooters with excellent hearing protection still develop anticipatory flinch patterns because their bodies are reacting to the pressure wave, not the sound.

Suppressors fundamentally alter this dynamic. By trapping and gradually releasing propellant gases, they eliminate the sharp pressure spike that creates the shockwave. The result is a shooting experience that your body doesn’t interpret as a repeated physical threat. This matters more than most shooters realize, particularly for those who shoot frequently or work on precision fundamentals.

Recoil Reduction That Actually Works

Here’s where suppressors deliver an advantage that surprises many shooters: genuine recoil reduction of 20 to 40 percent, depending on the cartridge and suppressor design. This isn’t just a perceived reduction or subjective feeling. It’s a measurable force reduction that stems from how suppressors manage propellant gas expansion. For example, a suppressed .308 Winchester that would normally deliver around 17 foot-pounds of recoil drops to 11 or 12 foot-pounds suppressed. That’s a 30 percent reduction that transforms the shooting experience, particularly over extended sessions.

The mechanics are straightforward. A suppressor captures expanding gases and releases them gradually through internal baffles. This process extends the time those gases push on the rifle system, which reduces the peak rearward force transferred to your shoulder. The forward weight of the suppressor provides a secondary benefit by dampening muzzle rise; however, the primary recoil reduction stems from gas management, not just the added mass.

The nature of the recoil impulse changes as well. An unsuppressed rifle delivers a sharp, sudden push to the rear. A suppressed rifle stretches that same energy across a slightly longer duration, creating a recoil impulse that feels more like a push than a punch. Combined with the actual force reduction, this creates a shooting platform that’s significantly more manageable. I can stay on target better, recover faster between shots, and maintain proper form with less conscious effort. These advantages accumulate over the course of a range session or a day in the field.

Situational Awareness in the Field

Hunters often focus on how suppressors protect their hearing during the shot, but the real advantage lies in what happens before and after the shot. Hunting suppressed transforms the entire experience by preserving your ability to observe the environment throughout the process.

When you’re not anticipating a painful blast, you don’t instinctively clench up before the shot. You remain relaxed and focused on the target. After the shot, you can immediately hear the animal’s reaction, the direction it runs, or whether it drops to the ground. This real-time auditory feedback is invaluable for making quick follow-up decisions.

I’ve taken game with both suppressed and unsuppressed rifles. The difference is stark. Shooting unsuppressed, even with hearing protection in place, temporarily deafens you to the environment. You’re often left wondering which direction the animal went, whether you heard a crash indicating a quick death, or if you need to prepare for tracking. Shooting suppressed, you hear everything. The sound of the bullet’s impact, the animal’s reaction to the shot (such as a hog’s squeal or a coyote’s bark), and the direction of movement. This immediate feedback has helped me recover animals faster and make better decisions in the field.

The same principle applies to predator calling or any hunting scenario requiring continued situational awareness. You can take a shot and immediately know if more predators are approaching, if more hogs are in the area, or if you need to reload quickly for a follow-up shot.

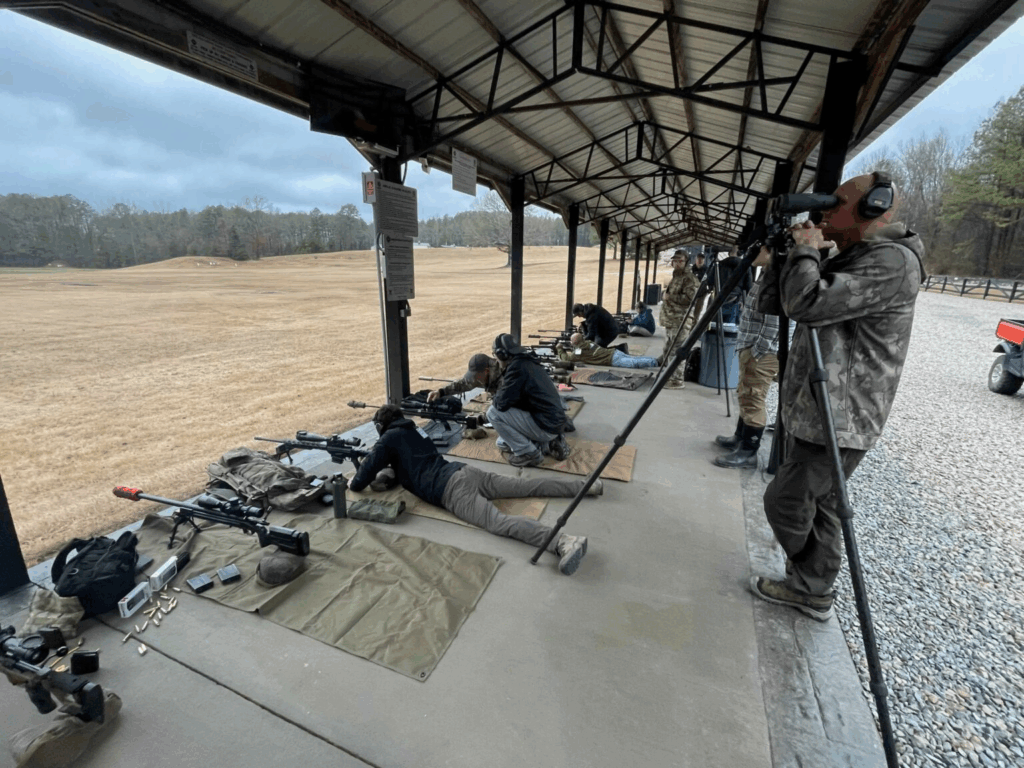

Training Efficiency and Shooter Development

New shooters develop bad habits remarkably fast when shooting creates physical discomfort. The combination of loud noise, blast pressure, and sharp recoil teaches beginners to flinch, tense up, and anticipate pain rather than focus on fundamentals. Quality instruction helps, but physiology fights against good technique when every trigger press delivers an unpleasant sensory experience.

I’ve introduced several people to shooting using suppressed rifles as their first experience. The results speak clearly. They learn proper trigger control more quickly, develop better breathing patterns, and maintain a relaxed body position more naturally. Without the physical intimidation factor, they can concentrate on sight picture, trigger press, and follow-through rather than bracing for impact. They also really enjoy the experience.

Even experienced shooters benefit from suppressed training. When you remove the blast and soften the recoil characteristics, you can diagnose technical problems more accurately. Is that flier caused by a flinch response or by an actual technique breakdown? With a suppressor, the answer becomes clearer because you’ve eliminated one major variable that masks or creates many shooting problems.

The Cumulative Fatigue Factor

Shooting is physically demanding in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. The repeated assault of muzzle blast, recoil, and noise creates cumulative fatigue that degrades performance over time. This matters whether you’re shooting a weekend precision rifle course, conducting serious practice sessions, or spending a day sighting in multiple rifles before hunting season.

I’ve noticed that my accuracy and focus hold longer when shooting suppressed. By the end of a hundred-round practice session with an unsuppressed rifle, I’m mentally tired and physically worn down. The same session with a suppressed rifle leaves me fresher and more capable of maintaining good technique throughout. The difference isn’t dramatic on a shot-by-shot basis, but it compounds significantly after several hours.

Beyond the Numbers

Decibel measurements provide useful data points for understanding suppressors, but they fail to capture the complete physiological experience. The elimination of blast shockwave, the reduced recoil characteristics, the preserved situational awareness, and less cumulative fatigue combine to create advantages that extend far beyond simple hearing protection.

For serious shooters and hunters who spend a significant amount of time behind their rifles, these factors represent real improvements in both performance and enjoyment. A suppressor doesn’t just make shooting quieter; it also reduces the recoil. It makes shooting fundamentally more comfortable, more controlled, and more conducive to developing and maintaining excellent technique. That’s the hidden advantage the decibel numbers never quite explain.

More on TTAG:

Read the full article here