The Japanese Submariner Who Became America’s First WWII Prisoner After Pearl Harbor

On the morning of Dec. 8, 1941, Sergeant David Akui walked along Waimanalo Beach and spotted what he thought was a sea turtle emerging from the surf. Akui quickly realized he had found something far more significant—a Japanese naval officer from the previous day’s Pearl Harbor attack. Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki became Prisoner of War No. 1 for the United States, the first of only approximately 50,000 Japanese military personnel who would surrender to Western Allied forces during World War II.

Sakamaki was the sole survivor among 10 Japanese submariners who attempted to penetrate Pearl Harbor in five two-man midget submarines. His survival marked him for disgrace in a military culture governed by Bushido, the warrior code that demanded death before surrender.

The Submarine Attack at Pearl Harbor

The Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor involved more than just carrier-based aircraft. Five Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines launched from larger mother ships positioned around 10 miles off Oahu. Each 78-foot submarine carried two torpedoes and a two-man crew. The submarines were supposed to enter the harbor before dawn, hide on the ocean floor, then surface during the aerial attack to fire torpedoes at the American battleships.

The plan was would be the first test of Japan’s secret midget submarines. Flight commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who led the aerial assault, opposed including the submarines though. He worried they would compromise the operation’s secrecy if spotted trying to enter the harbor before the bombing. His concerns proved valid when the USS Ward sank one of the submarines at 6:37 a.m.—more than an hour before the first bombs fell. However, American commanders dismissed the Ward’s report as a false alarm.

Sakamaki commanded HA-19, launched from submarine I-24 at 3:30 a.m. with Chief Warrant Officer Kiyoshi Inagaki as his crewmate. Their submarine’s gyrocompass failed immediately. Navigation became guesswork. Sakamaki had to expose the periscope frequently, risking detection from multiple patrolling American ships. HA-19 struck coral reefs three separate times trying to reach the harbor entrance.

At 8:17 a.m., only minutes after the bombing of Pearl Harbor began, the destroyer USS Helm spotted HA-19 stuck on a reef and fired. The shells missed but the concussion knocked Sakamaki unconscious and freed the submarine from the rocks. The impacts had crushed the forward torpedo tubes. Seawater leaked into the battery compartments, producing chlorine gas that repeatedly knocked both men unconscious as they drifted east around the island.

American destroyers dropped depth charges on the crippled submarine throughout the day. By evening, HA-19 had grounded near Bellows Field. The men awoke and set scuttling charges to destroy the submarine, then they both abandoned ship. However, the explosives failed, likely having been flooded by the seawater. Inagaki drowned fighting through the surf while Sakamaki washed ashore unconscious.

Bushido and the Shame of Capture

Bushido, the samurai code adapted for modern Japanese military service, required warriors to die rather than accept the dishonor of surrender. The 1941 Senjinkun military code specifically prohibited Japanese soldiers from being taken prisoner. Ritual suicide through seppuku offered the traditional path to restore honor after failure or capture.

In reality, this mindset was the Japanese military’s attempt to mask their lack of modern equipment and resources to wage war, opting to sacrifice service members in last ditch attempts to overwhelm superior enemies through banzai charges and suicidal attacks. These lessons were learned the hard way after Japan’s humiliating skirmishes with Soviet forces in Manchuria.

This indoctrination, however, proved effective. Despite approximately 50,000 Japanese military personnel eventually surrendering during the war, the vast majority fought to the death. Of the roughly 27,000 American POWs held by Japan, more than 11,000 died in captivity—a death rate exceeding 40 percent. Japanese forces expected equal brutality from the Allies and preferred death to potential torture.

After finding Sakamaki on the beach, Cpl. Akui and Lt. Paul. G. Plybon tied him up and placed him in the back of a jeep.

When Sakamaki woke up in a hospital under guard, he immediately requested means to commit suicide. American authorities refused. Japanese high command struck his name from official records and informed his family his status was unknown, though they were aware he had been taken prisoner. The nine other submarine crewmen received posthumous double promotions and became national heroes while Sakamaki was left out of propaganda posters and memorials.

Fuchida later noted in his autobiography that “the Navy scrubbed the face of officer Sakamaki from a photo taken with the nine other crew members before they were sent out.”

Sakamaki spent nearly three months confined to a small cell on Sand Island in Honolulu Harbor. He considered suicide constantly during those first weeks. Like other Japanese soldiers captured during the war, the shame of capture was unbearable for him.

Life as a Prisoner in the United States

American authorities transferred Sakamaki to mainland POW camps. He spent time at facilities in Wisconsin, Camp Livingston in Louisiana, and numerous other locations. Military intelligence interrogated him extensively. His submarine had been captured intact with documents and charts that revealed detailed planning of the Pearl Harbor attack.

However, he was treated with fairness and even kindness by his captors and was fed well, the complete opposite of what he had anticipated. Faced with indefinite imprisonment with this treatment, Sakamaki chose to continue living and gave up on his goal of committing suicide. He learned English and eventually became a leader among Japanese POWs, encouraging other captured servicemen to adapt rather than attempt suicide. He eventually devoted himself to pacifism.

“For what reason is it justifiable to say that Japanese military personnel who were taken as prisoners are unpatriotic and deserve death?” Sakamaki later wrote in one of his memoirs.

Between 35,000 and 50,000 Japanese military personnel would be held as POWs by Western Allies before war’s end. Sakamaki’s role as the first gave him a unique status among the other captives. He later expressed gratitude that he was able to convince many other prisoners to change their mindset during this time.

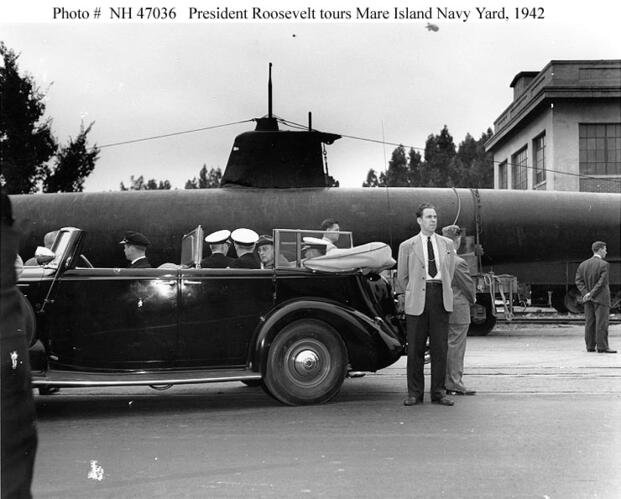

Meanwhile, his submarine served American propaganda purposes. The Navy disassembled HA-19, installed viewing ports in the hull, and placed mannequins in Japanese uniforms inside. The submarine toured through 2,000 cities and towns across 41 states between 1942 and 1945. Americans bought war bonds for the privilege of viewing it. The campaign raised millions for the war effort.

Post-War Return to Japan

Sakamaki returned to Japan in January 1946, finding his homeland bombed, devastated, and occupied by American troops. The reception he received from his fellow countrymen was hostile. Strangers sent him countless letters demanding he perform seppuku to atone for his shame. One letter stated, “The souls of the brave comrades who fought with you and died must be crying now over what you have done.”

His family had been told to keep his possible survival secret during the war. When the truth emerged, Sakamaki faced social ostracism, like countless other survivors. On Aug. 15, 1946—the first anniversary of Japan’s surrender—he married a woman whose father and brother had died in the Hiroshima atomic bombing. Their shared losses may have created understanding of the war’s costs.

Sakamaki later joined Toyota Motor Corporation, where his English skills proved valuable in export sales. He rose to become president of Toyota’s Brazilian subsidiary in 1969. His eldest son was named Kiyoshi, likely in memory of his drowned crewmate. However, Kiyoshi was also criticized by his peers for being the son of a “coward.”

Akui went on to fight in the Pacific Theater of WWII and even served with the famous “Merrill’s Marauders.” He refused multiple chances to again meet with Sakamaki during and after the war. Lt. Plybon was killed in action later in the war.

For 45 years, Sakamaki refused to discuss his wartime service publicly, though he privately published his memoirs. After learning the origin of his name, Kiyoshi went on to lecture about his father’s experiences and urge understanding and forgiveness for men who had been through such extreme events.

In 1991, Sakamaki attended a historical conference at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas. The museum had acquired HA-19 for permanent display in its exhibits. When Sakamaki encountered his submarine for the first time in 50 years, he broke down in tears.

He died in Japan on Nov. 29, 1999, at age 81. He had survived disgrace, imprisonment, and social condemnation to build a successful life as a pacifist and businessman. His submarine remains at the Texas museum, one of five midget submarines that participated in Pearl Harbor’s often-forgotten submarine assault.

Story Continues

Read the full article here